Immigration and Justice

- Daniela Gerson

- Apr 28, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 17, 2025

-As published in the New York Times / Opinion. April 26, 2021. Used with permission

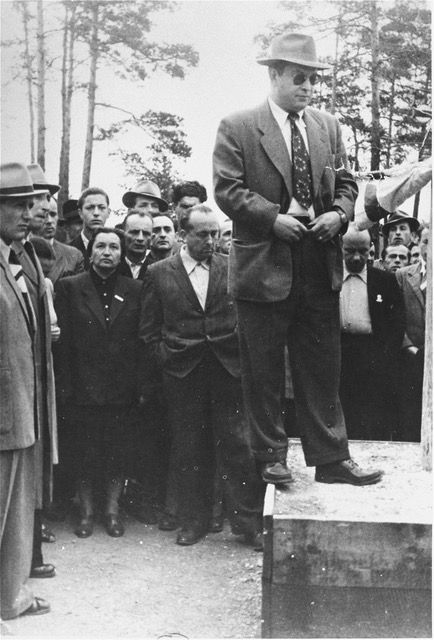

Illustration by The New York Times; photographs from the Gerson Family

By Daniela Gerson Ms. Gerson is an assistant professor of journalism at California State University, Northridge, and a co-founder of Migratory Notes, a weekly immigration newsletter.

I felt like I was spying on my grandparents’ lies. “The Blumstein family, consisting of Mr. B, age 43, his wife, same age, and their two children, ages 6½ and 2½ arrived in the United States on 12/21/50,” begins the social worker’s minutely detailed account of my grandparents’, and my father’s, first weeks as refugees in the United States. But my grandparents and their children weren’t the Blumstein family. The Blumsteins were in Israel. The Jewish refugee family — described by the attentive social worker as “attractive” and “charming,” who arrived with $30 in cash and a baby’s bathtub — were the Gerzons. The child traveling as Abraham Blumstein, 6½, was a 5½-year-old whose birth name was Elik. He was my father. His identity, along with his parents’, had been erased for a chance to enter the United States. Nearly 70 years later, in what would turn out to be my father’s final year, he was working furiously on a memoir. It was as if he already knew a rare and ruthless neurodegenerative disease would eat away at his mind. In those final lucid months, rather than focus on the professional legacy that would later headline his obituaries — he was well known in Washington for his work carving a legal path to sue foreign countries for sponsoring terrorism, most famously in the case of Pan Am Flight 103 — he wrestled with personal questions of ethics and immigration law. My father knew all too well what happens when legal pathways do not exist for people to enter this country: They find alternative ways in, just as his own family had. As refugee admissions remain at historic lows, my father is no longer with us. But he left behind a warning that changes need to be made to immigration laws, seeded in the unlikely intersection of the lies of his parents, Holocaust survivors both, and his early career turn as a Nazi hunter for the U.S. government. My father was born stateless in Uzbekistan in 1945, as World War II was winding down. His Polish-born Jewish parents had spent years in flight — first to Russia in 1939, when Hitler invaded their home country, only to be deported via cattle cars into forced labor in Siberia. My father’s older brother perished of diphtheria during the war. Postwar, my grandparents boarded trains west, but at the Polish border heard the news that nearby villagers had murdered Jews who returned and gave up on their plan to reclaim their home. So began the lies of desperation. For five years, the Gerzons languished in displaced persons camps in Austria and Germany. They heard Foehrenwald, in the American zone of Germany, both had better conditions and bettered their chance of receiving a visa to enter the United States. But the door to the camp was shut. On the black market they found a way in: The Blumsteins, a family like them, had received permission to enter the camp but instead left for Palestine. The Gerzons thus bought the identities — and opportunities — of the Blumsteins. Once inside Foehrenwald, fearful of the consequences of their fraud, they continued their quest for safe haven in the United States under their assumed names. In 1950, President Harry Truman finally broadened quotas enabling more Polish Jewish displaced persons like them to enter. That December they arrived in New York Harbor. Once in the United States, my father and his brother weren’t told their true names. For the next six years he would be known as Abie Blumstein. Mystified about why he was not preparing for his bar mitzvah, he pressed his parents until he finally learned the truth. His parents, with the help of a lawyer, took the chance of exposing their fraud to be naturalized under their real names and began anew. As he turned 13 he was able to choose an American name for himself: His third and final name would be Allan Gerson. If my father’s family had a guiding ethos, it was “Never forget, never forgive.” In 1979, as a trial attorney at the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations (O.S.I.), my father had an opportunity to live those words. He was tasked with hunting Nazis. My father should have felt great satisfaction in his role; he was, after all, avenging the gassing deaths of his cousins, aunts and uncles, grandparents, making men pay for the terror that haunted his parents. Yet, the shadow of his own family’s lies quickly made him question the government’s tactics. It turned out that the immigration trespasses of those who could have marched my great-grandparents to their deaths, from a legal perspective, were often not so different from those of my grandparents. Both were guilty of material misrepresentation. My father did not prosecute Nazis based on their wartime crimes, but rather because they had lied on immigration forms about their role in assisting in persecution of civilians. Never mind that many were low-level Nazi collaborators who faced death if they did not follow the sergeant in charge. The consequences of deporting someone labeled a Nazi to the Soviet Union, where many of those prison guards recruited from formerly Nazi occupied countries would have been returned, were not considered. “Misrepresentation in visa and citizenship applications is a matter of U.S. immigration law, and few if any of the normal due process rights accorded to defendants in criminal trials apply,” my father wrote in his memoir, “Lies That Matter,” which will be published next month. “And so deportations to the U.S.S.R. followed by a firing squad were seen as not really ‘punitive,’ as if lives were not at stake.” To my father this was not justice: The immigration system did not take into consideration whether the punishment fit the crime. He left O.S.I. after 18 months. Make no mistake, my neoconservative father was no bleeding heart backer of open borders. In 1986, the year President Ronald Reagan provided permanent legal status for 2.7 million immigrants, my father left his job as senior counsel to the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and moved to the Office of Legal Counsel at the Department of Justice, but immigration does not appear in his writing on the period. I do remember a moment, a few years later, as we watched nightly news reporting on asylum seekers on boats coming from Haiti. “We can’t let them all in,” said my father, as he explained the situation to me. Yet, in his later years, he identified increasingly with the plight of minors without legal status, brought to the United States like him under the cover of their parents’ lies. “I was an illegal immigrant,” he wrote in The Washington Post in 2017. “I was little different from those who bear the designation dreamer today.” It wasn’t the first time he saw himself in these stories. A few years earlier, he took on the case of a Honduran asylum seeker acquaintance who maintained he would face extortion and execution by the local police if deported. My father lost the case, shocked by the lack of discretion judges have in immigration court and the overall chaos of the system. My father had come to recognize that in contrast to what so many of today’s most vulnerable immigrants face, the system his family encountered ultimately supported them. He also knew intimately that lives are at stake. As my father warned us in his final writings, if the United States does not create a legal system for immigration that understands what desperation pushes people to do, and creates just responses, everyone loses. Daniela Gerson is an assistant professor of journalism at California State University, Northridge, and a co-founder of Migratory Notes, a weekly immigration newsletter. The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com. Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.

Comments